In 2008, an annual earthquake drill known as the Great ShakeOut began in Southern California to teach the basic safety technique of "drop, cover and hold on." Initially based on a scenario of a magnitude 7.8 quake on the southern end of the mighty San Andreas fault, the drill has since spread across the United States and around the world.

In 2015, Los Angeles enacted a mandatory retrofit ordinance aimed at preventing loss of life in major earthquakes at the city's most vulnerable buildings. It covered about 13,500 "soft-story" buildings like Northridge Meadows and some 1,500 buildings with "non-ductile reinforced concrete" construction. The ordinance, however, allowed a process spanning seven years for retrofitting of soft-story buildings and 25 years for non-ductile reinforced concrete buildings.

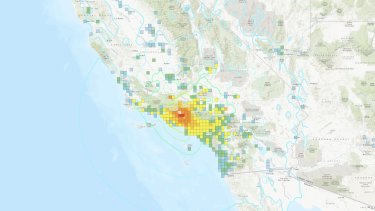

Seismic hazard mapping has changed significantly since 1994. The maps help evaluate earthquake hazards and the risks they pose to parts of the United States. The more advanced models take what researchers know about earthquake sources, crust deformation, faults and ground shaking and help create seismic hazard maps used for seismic requirements in building codes and risk models for insurance rates.

Researchers are able to better document faults in the Los Angeles area -- what seismologist Dr. Lucy Jones called a "CAT scan" of the LA basin. The models allowed researchers to study the Oakridge fault, a larger fault that shows up in Ventura County.

"We could start seeing that Northridge wasn't just a localized little fault," Jones told NBC4 in a 2019 interview. "Up until Northridge, we would have said you couldn't have that big an earthquake on a blind fault -- that if it's a big enough fault to give you a big earthquake, it has to come all the way through to the service. We had to revise that idea."

USGS earthquake event pages provide the public with critical information. They are a go-to resource with detailed information about individual earthquakes and answer the question on everyone's mind when we feel shaking: Was that an earthquake? The best place to go for an answer is this USGS map of latest earthquakes.

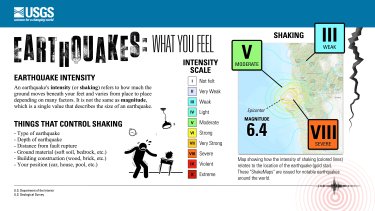

The word "magnitude" is often used to describe the size of an earthquake, but it doesn't take into account all factors that influence what we feel during an earthquake. The Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale (MMI) offers something more relatable depicted on a scale of intensity ranging from "Not felt" to "Extreme." Factors that control shaking include the type of earthquake, its depth, distance from the fault rupture, the type of ground material in the area, building construction and where you are at the time, such as in a house, car or swimming pool. MMIs are included on the USGS earthquake event pages.

Earthquakes and aftershocks can't be predicted, but seismologists can use statistical probabilities to provide a forecast -- an idea of what to expect after the main event. The USGS Aftershock Forecast wasn't around in 1994, but now it's available to the public on each USGS event page -- something that also wasn't available 30 years ago -- for quakes larger than mangnitude-5.0. The forecast offers the probability of small, medium and large earthquakes, and an idea of how many aftershocks to expect.

In 2014, the Los Angeles Economic Development Corp. released a guide aimed at helping businesses minimize disruptions from major earthquakes, taking advantage of information technologies such as the digital cloud to keep a company working even if its physical systems are destroyed or inaccessible.